This iconic shot of a beautiful little leaping New Zealand dolphin is by marine scientist Will Rayment

The New Zealand government is willfully allowing the extinction of their own native dolphin species, the endangered Hector’s dolphin (Cephalorhynchus hectori) and the critically endangered Maui's Dolphin (Cephalorhynchus hectori maui). New Zealand marine scientist Dr. Elisabeth “Liz” Slooten (WhaleDolphinTrust.org.nz) is doing everything she can to stop it.

A member of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature Cetacean Specialist Group (www.iucn-csg.org) and former New Zealand representative on the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission (www.iwc.int) and the Otago University Marine Mammal Research Group (www.otago.ac.nz), Slooten is a tireless researcher and the world’s leading expert on New Zealand’s native Maui’s dolphin, whose population has plummeted from 2,000 in 1970 to about 50 today. That perilously low number means the species could go extinct at any moment; the only two classifications worse than “critically endangered” are ”extinct in the wild” and “extinct.” Period. End of story. At this critical moment in history, the world needs to wake up quickly and pressure New Zealand do something before it’s too late.

Slooten is waking up the world with indisputable science about how shockingly unsustainable gill and trawl net fishing methods, which catch the dolphins in nets and kill them as “bycatch,” are pushing the dolphins into extinction. “What is it about the words ‘critically endangered’ that the decision-makers don't understand?” she says. “This extinction is totally avoidable.”

Because the current government in New Zealand refuses to protect the dolphins, the nation’s upcoming 2014 General Elections (www.elections.org.nz) on September 20 will be a critical moment for the their survival. Animal rights activist and correspondent Zoe Helene talks to Slooten about what’s at stake.

Is it true that the powers-that-be in the New Zealand government are knowingly supporting the extinction of New Zealand’s only endemic species of dolphin? And that they’ve been fully aware of the rapid decline since 1970?

Yes. The population is declining rapidly. There were 140 in 1985, 111 in 2004. Right now there are only about 50 left—some 20 breeding females!

When did the crisis first come to light?

We first started to realize this was a problem in the 1970s. By the mid 1980s it was abundantly clear that Hector’s and Maui’s dolphins were declining rapidly due to bycatch. The first draft of a recovery plan for Hector's and Maui's dolphins was written in the 1990s.

Roughly, what are the statistics of decline?

Hector's dolphins have declined from around 30,000 individuals in 1970 to fewer than 8,000 today. Maui's dolphins have declined from around 1,000 individuals to fewer than 80 individuals today (the latest population estimate is 50).

There are only two classifications worse than “critically endangered,” and they are “extinct in the wild” and “extinct,” full stop. Could the species go extinct?

The Maui’s dolphin could go extinct at any moment and certainly within a decade or two if we keep killing them in fishing nets. Hector’s dolphins would continue to slide from “endangered” to “critically endangered.” Several Hector’s dolphin populations (e.g. on the north and south coasts of the South Island) are already in the same situation as Maui’s dolphin.

It’s incredibly urgent to allow the Maui’s dolphin population to recover to at least several hundred individuals as soon as possible. Every day that they remain at the dangerously low population size where they are now is another very serious risk. They could disappear at any time, without further warning.

This extinction would set a precedent. New Zealand would go down in history as the first nation to extinguish a marine dolphin.

The Maui's dolphin would be the first marine dolphin to go extinct at the hands of humans. Even during the great whaling era, humans didn’t quite manage to completely wipe out any whale or dolphin species.

New Zealand is already infamous for wiping out the Moa (Dinornis robustus) and the Haast's Eagle (Harpagornis moorei). The Maui's Dolphin (Cephalorhynchus hectori maui) would be the third human-caused extinction in New Zealand. As a New Zealander, how does that make you feel?

Ashamed. Many international marine mammal scientists are looking to New Zealand to do the right thing. Really, if we cannot protect a critically endangered species that is found only here in New Zealand, then we might as well all go home and give up.

Is this extinction avoidable?

This extinction is totally avoidable. We don’t even need to do anything complicated like habitat protection, supplementary feeding or anything like that. All we need to do is stop killing these dolphins in fishing nets. We don’t even need to stop fishing. Selective, sustainable fishing methods are already available. Making the transition to these dolphin-safe fishing methods would benefit not only dolphins but also seabirds, sharks and fish. Within a few years this would actually bring economic benefits to the New Zealand fishing industry. They are just stuck in denial and thinking only about short-term profits rather than the long-term survival of their own industry.

Resources for Helping to Save New Zealand's Native Dolphin ♥ “Unlike humans, dolphins actively decide to breathe. When humans are knocked unconscious, they keep breathing. An unconscious dolphin stops breathing. They usually just don’t breathe and run out of air. Drowning is not a nice way to die. A dolphin caught in a net struggles madly to try to escape. At the end of this struggle, the dolphin suffocates. It would take up to five minutes or so to die. ” - Liz Slooten

Resources for Helping to Save New Zealand's Native Dolphin ♥ “Unlike humans, dolphins actively decide to breathe. When humans are knocked unconscious, they keep breathing. An unconscious dolphin stops breathing. They usually just don’t breathe and run out of air. Drowning is not a nice way to die. A dolphin caught in a net struggles madly to try to escape. At the end of this struggle, the dolphin suffocates. It would take up to five minutes or so to die. ” - Liz Slooten

Are there ways to fish without harming the dolphins?

Yes, absolutely! Many alternative fishing methods are available. These include fish traps and a range of hook-and-line methods. These are already being used around New Zealand and in other parts of the world. The vast majority of marine recreational fishers (a ministry of fisheries study estimates more than 90 percent) do not use gillnets. Changing to selective, sustainable fishing methods will benefit not only dolphins, but also seabirds and fish stocks. This will be in the long-term economic interests of the fishing industry.

The last time the New Zealand government put significant protective measures in place, the SeaFood Industry Council (SeaFIC) (www.seafood.co.nz), New Zealand’s coalition of seafood industry corporations, sued for “loss of revenues.” For a remote island country with just shy of 4.5 million citizens, SeaFIC seems like an overwhelming force. Do you feel free to speak openly to national and/or international media?

Sure, I speak out openly. As a scientist, I base my comments on the biological reality of the situation. The problem is that the decision makers are not really interested in the science.

In an ideal situation, what protection measures need to be in place to save both the Hector’s and Maui’s dolphins?

Every relevant group of scientists in New Zealand and internationally has now supported protection for Hector's and Maui's dolphins out to the 100-meter depth contour.

Does the government understand this?

The current government has ignored advice from the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission (www.iwc.int/scmain), (200 international whale and dolphin experts), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (www.iucn.org) and the IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group (www.iucn-csg.org) (about 100 members) the Society for Marine Mammalogy (www.marinemammalscience.org) (2,000 members) and the New Zealand Marine Sciences Society (nzmss.org) (about 250 members). All of these scientists agree that Maui’s dolphins and the species as a whole (Hector’s dolphins) range offshore to the 100-meter depth contour. The scientific consensus is that Hector’s and Maui’s dolphins should be protection to the 100-meter depth contour (or at least to 20 nautical miles offshore).

New Zealand’s SeaFood Industry Council’s positioning statement is basically, “we simply don’t have enough good independent data on the dolphins.”

After more than 30 years of research on Maui's and Hector's dolphins, there’s more than enough scientific data showing their population number and reasons they’re in rapid decline. The Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission (www.iwc.int/scmain) recommended last year that there should be no more research done on Maui’s dolphins. They repeated the same advice this year. The New Zealand government has totally ignored the IWC recommendations.

In fact, we have much more data on this conservation problem than for almost every other dolphin in the world. Dr. Andy Read (www.nicholas.duke.edu/people/faculty/read), a marine mammal scientist from Duke University, visited New Zealand a few years ago and said exactly that. In a talk to New Zealand decision makers, he said the Hector’s dolphin was an “exceptionally well-studied species” and the time had come to act and protect these dolphins. Likewise, the Society for Marine Mammalogy (www.marinemammalscience.org), in a letter to the New Zealand government in January 2013, said that, “Scientists from New Zealand and elsewhere have provided an exceptionally strong scientific basis for managing fisheries to prevent the extinction of Maui's dolphins.” This is not the time to continue to call for “more research.” This is the time to put in place effective protection measures.

How does echolocation work and why can’t dolphins use it to detect nets?

Dolphins use echo-location to locate their prey – it’s like seeing with sound. Dolphins send out a stream of high-frequency clicking noises, and when the sound strikes an object it bounces back and the dolphin can tell by listening what the object is—what kind of fish it is, how far away it is and how fast it’s moving. In familiar areas, their echo-location is turned off, which means they cannot always detect dangers.

What happens when a dolphin drowns in one of these nets?

Unlike humans, dolphins actively decide to breathe. When humans are knocked unconscious, they keep breathing. An unconscious dolphin stops breathing. They usually just don’t breathe and run out of air. Drowning is not a nice way to die. A dolphin caught in a net struggles madly to try to escape. At the end of this struggle, the dolphin suffocates. It would take up to five minutes or so to die.

Do other dolphins try to help the dolphin that’s caught in the net?

If there are other dolphins around they will often try to release the entangled dolphin. We’ve seen one dolphin that had died in a gillnet that was covered in fresh toothrakes, many of which were bleeding. It seems that the other dolphins in the group tried to get this dolphin out of the net and failed. We have also seen a dolphin calf that was caught in a net with a lot of toothrakes on it, indicating that the mother had tried to get her calf out of the net. That was such a sad sight.

Resources for Helping to Save New Zealand's Native Dolphin ♥ “The calf needs a couple of years with mum, to learn how to use its sophisticated echolocation system, find fish, avoid sharks, the social rules of dolphin society and other important survival skills. These are very sophisticated animals in terms of their biology, communication system and social organization. Like humans, much of this information is learned.” - Liz Slooten

Resources for Helping to Save New Zealand's Native Dolphin ♥ “The calf needs a couple of years with mum, to learn how to use its sophisticated echolocation system, find fish, avoid sharks, the social rules of dolphin society and other important survival skills. These are very sophisticated animals in terms of their biology, communication system and social organization. Like humans, much of this information is learned.” - Liz Slooten

What happens to an orphaned baby dolphin when his or her mother drowns in a net?

Usually an orphaned calf dies.

Many—maybe even most—people don’t understand that other species teach their children, just like we do.

The calf needs a couple of years with mum, to learn how to use its sophisticated echolocation system, find fish, avoid sharks, the social rules of dolphin society and other important survival skills. These are very sophisticated animals in terms of their biology, communication system and social organization. Like humans, much of this information is learned.

The New Zealand Department of Tourism (www.tourismnewzealand.com) is funded and controlled by the National Party (www.national.org.nz), the current party in power in Parliament, led by Prime Minister John Key (www.johnkey.co.nz). Key is also the (self-appointed) Minister of Tourism. In light of the readily available information around this issue, his “100% Pure New Zealand” (www.newzealand.com) international advertising campaign seems painfully hypocritical and intentionally misleading. How long do you think it will take for intelligent tourists to wake up to this?

Many tourists are already waking up to this. I think this will start to hurt the tourism industry within a few years, unless the government gets serious about protecting its endemic dolphins. If we lose our reputation as a clean, green, sustainable country, this will also make people overseas reluctant to buy any New Zealand products.

Strictly from a savvy business/brand perspective, it seems rational to flip the situation around and not only protect the dolphin but promote the dolphin as a treasure found only in New Zealand?

Absolutely. We are looking to green business leaders to help with this.

Does pressure from outside of New Zealand help?

So far, international pressure has had a much stronger effect than local pressure. It's partly to do with New Zealand's desire to become a member of the United Nations Security Council (www.un.org/en/sc). New Zealand is very sensitive to any criticism from other countries but almost completely insensitive to the wishes of its own citizens.

People outside New Zealand can write to prominent politicians (and/or newspapers, blogs, Facebook sites, etc.) to say that if New Zealand doesn't immediately protect its endangered, endemic dolphins, then they will cancel their next holiday to New Zealand and stop buying New Zealand fish and other New Zealand products.

Why don’t more New Zealanders know about their own endemic dolphin? Why isn’t this common knowledge, and something to be proud of? Why isn’t it taught in schools? What’s the disconnect—really?

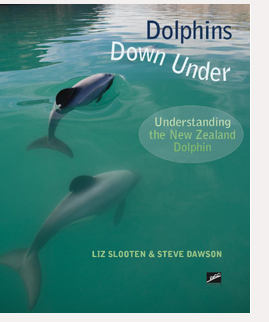

That’s a good question. There certainly are a lot more people who know about them now. The book Dolphins Down Under: Understanding the New Zealand Dolphin (www.amazon.com) has helped, and there’s a lot of discussion online and lots of public talks. But still, a surprising number of people don’t seem to know about New Zealand’s own dolphin.

What can New Zealand citizens do to help?

Please vote!!!

From the dolphin’s perspective, how important is the general election on September 20?

This election is extremely important. The National Party has made it very clear that it will do nothing more to protect Maui's or Hector's dolphins. Therefore, if they get back into government, there will be no progress. Hector's dolphins may be sufficiently large to cope with another three years of population decline. Maui's dolphins would be very unlikely to make it.

If we get a change of government, that would change everything. We will either end up with a continuation of the current, right wing government dominated by the National Party or we may end up with a left-wing government that includes the Labour Party (www.labour.org.nz) and several smaller parties including the Green Party (www.greens.org.nz), Maori Party (maoriparty.org) and Internet Mana Party (mana.net.nz). Labour Party politicians have put in place 94 percent of the protection for Hector’s and Maui’s dolphins.

Young Kiwi voters could rock the vote in the upcoming Elections!

Only about 50 percent of young people in New Zealand vote. If we can get them to register to vote (ASAP) and then to actually vote (on 20 September), that would make a huge difference.

What about eating fish?

Provide information outside your supermarket or fish shop. Also, when you buy fish, ask how it was caught (and don't buy it if you don't get a sensible answer or the answer is “in a net”).

You’ve tirelessly focused on this issue for decades. Do you still have hope?

Absolutely! Things would have been much worse without the protection measures that have been put in place in the last 30 years. All we need now is one more push to ensure Maui’s dolphins are not lost forever and Hector’s dolphins don’t keep sliding toward the same fate.

—END INTERVIEW—

LEARN MORE ABOUT NEW ZEALAND'S NATIVE DOLPHINS

To learn more about the Hector’s and Maui’s Dolphin, check out Dolphins Down Under: Understanding the New Zealand Dolphin (Otago University Press, 2013), co-authored by Dr. Elisabeth “Liz” Slooten and Dr. Steve Dawson, scientific partners who have intensely studied New Zealand’s only endemic dolphins for more than 30 years. To support their work, please visit New Zealand Whale and Dolphin Trust, the leading authority on the Hector's and Maui's Dolphin and the only group actively researching their conservation.

To learn more about the Hector’s and Maui’s Dolphin, check out Dolphins Down Under: Understanding the New Zealand Dolphin (Otago University Press, 2013), co-authored by Dr. Elisabeth “Liz” Slooten and Dr. Steve Dawson, scientific partners who have intensely studied New Zealand’s only endemic dolphins for more than 30 years. To support their work, please visit New Zealand Whale and Dolphin Trust, the leading authority on the Hector's and Maui's Dolphin and the only group actively researching their conservation.

New Zealand is already infamous for wiping out the Moa (Dinornis robustus) and the Haast's Eagle (Harpagornis moorei). The Maui's Dolphin (Cephalorhynchus hectori maui) would be the third human-caused extinction in New Zealand. It would be the first marine dolphin to go extinct at the hands of humans. Even during the great whaling era, humans didn’t quite manage to completely wipe out any whale or dolphin species.

“What is it about the words ‘critically endangered’ that the decision-makers don't understand? This extinction is totally avoidable.” - Dr. Elisabeth “Liz” Slooten

Zoe Helene (zoehelene.com) is a media correspondent and advocate for women, wildlife and wilderness. She spent 10 influential years growing up in Aotearoa, the Maori word for New Zealand, which means The Land of the Long White Cloud. Zoe works with leading activists, scientists and environmental organizations across the globe to save species such as the critically endangered Maui's Dolphin and endangered Hector's dolphin from extinction. Hector’s and Maui’s are New Zealand's only native dolphins. Zoe, like the native Maori, considers them taonga, a treasure to protect and cherish.

PHOTO CREDITS

Photo of New Zealand Mother and Calf by Steve Dawson

Photo of New Zealand Dolphin Jumping is by Will Rayment

SOCIAL MEDIA

NZ WhaleDolphinTrust (@hectorsdolphin) | Twitter